Submission to the TGA Public Consultation: Reviewing the Safety and Regulatory Oversight of Unapproved Medicinal Cannabis Products

Australia has the opportunity to be a global leader in safe, balanced, and evidence-based regulation of medicinal cannabis. This requires moving beyond outdated prejudices, recognising the unique properties of natural therapeutics, and respecting the central role of the doctor–patient relationship. Over-regulation and prohibitionist tendencies will only drive use underground, increasing risks and reducing oversight.

The Case for Proportionate Regulatory Scrutiny of Emerging Therapeutic Peptides

Regulating emerging therapies should not proceed without a proportional analysis of the effect on patient outcomes and risks.

Health Practitioners Ombudsman ‘Immeadiate Powers’ Review

My experience with AHPRA Investigators and the Board - the motivation behind much of my advocacy and educational work.

Revised National Prescribing Competencies Framework (3rd Edition)

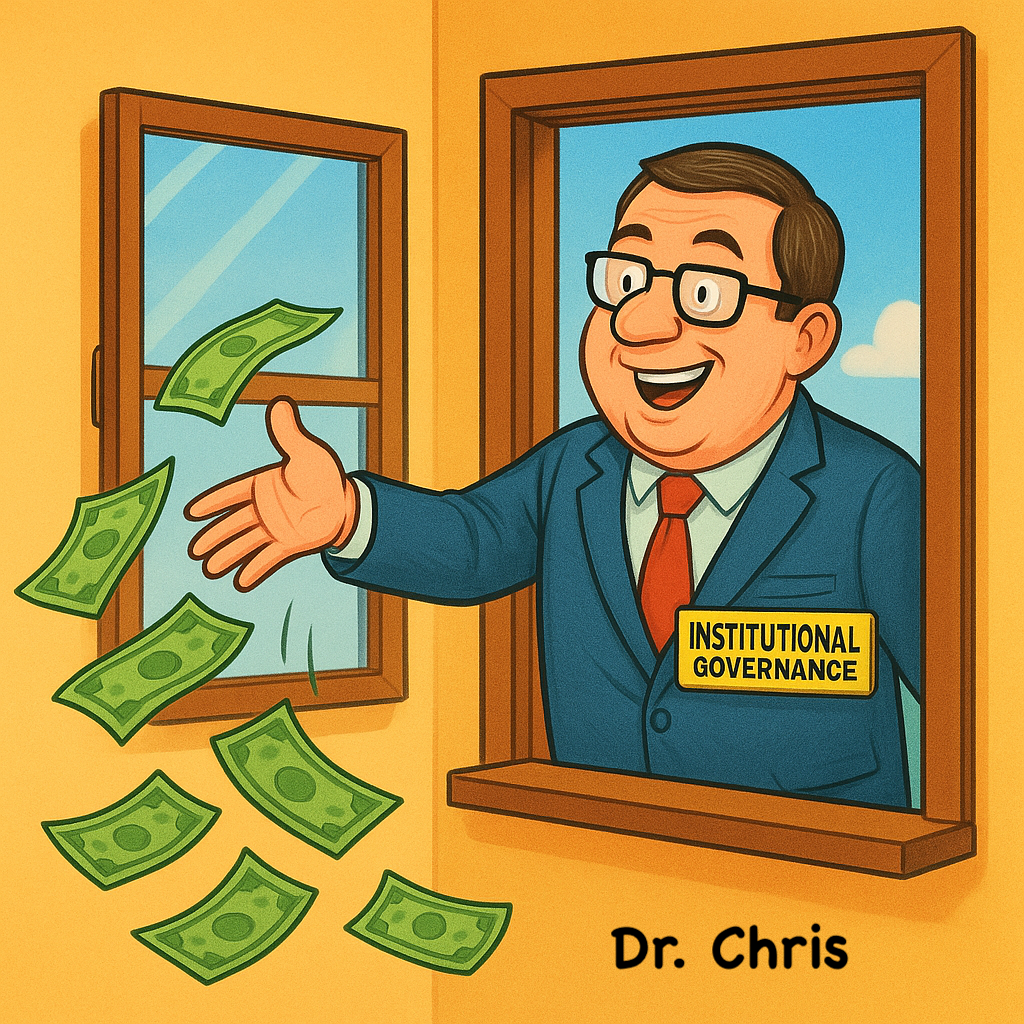

Is AHPRA spending money it doesn’t have doing things that are unlikely to affect patient outcomes?